Dave Whitworth, Junior Geologist.

As part of my PhD I travelled to the US to carry out some sedimentological fieldwork. The following will be part-technical article, part geoliday write up!

My study area was centred around Zion National Park in southwestern Utah – possibly the most beautiful place I have ever seen, and I’ve seen some truly fantastic landscapes on geology trips. My research focusses on the interactions between arid, continental sediments (mainly aeolian dunes) and marine incursions (mainly tidal flats and channels), the resultant products of those interactions preserved in the rock record, and their potential to act as reservoirs for carbon storage.

The first week of the trip I toured several localities across southern Utah with an experienced geologist and stratigrapher from the Utah Geological Survey. We looked at a proximal to distal transect through the Middle Jurassic Temple Cap Formation. The Middle Jurassic was characterised by an inboard seaway encroaching from the northwest, interacting with the well-known Navajo Sandstone of the Lower Jurassic. The Temple Cap Formation effectively records the transition between terrestrial Navajo dunes, and the marine carbonates of the overlying Carmel Formation.

Figure 1 shows one such outcrop of Navajo Sandstone, with the Temple Cap Formation atop its crest. The top of the Navajo sandstone is marked across much of southern Utah by an unconformity characterised by pedogenic chert nodules indicating paleosol formation.

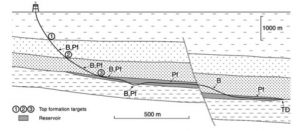

The Temple Cap Formation records a subsequent transgression (sea level rise), leading to the deposition of tidal flats, streams, and red beds – known as the Sinawava Member (Figure 2).

A brief return to desert conditions saw the deposition of coastal sand dunes (White Throne Member), which record dune collapse and brecciation at the coastline (Figure 3). Following another transgressive episode, the White Throne Member subsequently grades into marine calcarenites and limestones of the Carmel Formation.

The subsequent weeks of the trip focussed on data collection in the form of sedimentary logs, geophysical data, samples, and paleocurrent data. These will be used to construct a stratigraphic framework of the arid-marine margin, make broad observations about reservoir volume, and then enable some finer-grained study into the pore-scale characteristics of the rocks for use as carbon-storage reservoirs.