You may have seen in the press over the last few days articles about the discovery of a giant ‘sea dragon’ in the Midlands. A giant ichthyosaur fossil was discovered early last year in the Rutland Water reservoir, Leicestershire and it soon became apparent that it was of major importance for UK palaeontology. Details of the discovery and initial conservation of the specimen can be found in this interesting article written by Nigel Larkin, who is the palaeontological conservator for the specimen.

The ichthyosaur skeleton is the largest found in the UK to date, at 10m long, and is also the most complete specimen known within that size range (see image below). The fossil was excavated over two weeks in summer last year, and it is hoped to be cleaned and put on display in the future. The specimen has been identified as representing the species Temnodontosaurus trigonodon. It is the first definite example of this species to be found in the country, which is almost unknown outside of Germany. The specimen will be studied in detail by several researchers, the principal palaeontologist being Dr Dean Lomax, a specialist in ichthyosaurs (we acknowledge Dean and Nigel for the information cited above regarding the discovery and its importance).

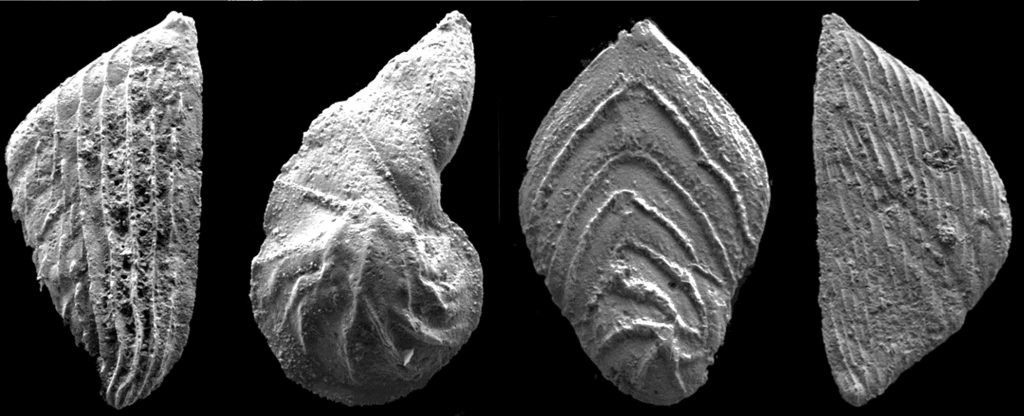

Here at Merlin, any new geological discovery is always of interest, especially when so close to home. However this time we have even more reason to shout about it as our very own stratigrapher, Dr Phil Copestake, was involved in dating the skeleton using associated microfauna. Phil is an expert in Jurassic foraminifera (the subject of his PhD) and has developed a biozonation scheme for the Lower Jurassic of North West Europe. In order to date the horizon at which the ichthyosaur specimen was found, samples were collected by Dr Ian Boomer (Birmingham University) from which a diverse microfossil assemblage was extracted. Phil and Ian have collaborated on many Jurassic micropalaeontology projects and in this instance were able to identify a distinctive foraminiferal assemblage that indicated that the bed in which the ichthyosaur occurred was of Early Toarcian (Serpentinum ammonite zone) age. The image below shows examples of Early Toarcian foraminifera. Elements of this assemblage had previously been recorded by the British Geological Survey in boreholes sited in the area of Rutland Water in the 1970s when the reservoir was being planned. In addition, in the sample, further species were found which confirmed this stratigraphic position, based on the established foraminiferal zonation scheme mentioned above. With this information it was then possible to infer a geochronological age of between 182 and 181.5 million years for the ichthyosaur, based on the most recent geological time scale. It is intended to publish the results of this research at some future date. In addition to the foraminifera, studies of calcareous nannofossils and palynomorphs are also being carried out by experts in these fields (Prof. Paul Bown at University College London and Dr Jim Riding of the British Geological Survey).

If you would like to learn more about the discovery and excavation of the ichthyosaur skeleton, it is featured on tonight’s (Tuesday 11th January) episode of Digging for Britain at 8pm on BBC2. The programme will be available on BBC iPlayer afterwards.